It has been sixty years between the idea to create a truly pan-European competition for football clubs and the Champions League final in Berlin between Barcelona and Juventus next week. But it has not been a linear evolution from the first tournament launched with sixteen clubs handpicked by the journalists from L’Equipe and today’s huge multi-million euro business. Right in the middle of these sixty years, on 29 May 1985, there was a traumatic watershed moment after which nothing was the same anymore. ‘The Heysel’, as the tragic event is still referred to today across the continent, has become a European lieu de mémoire.

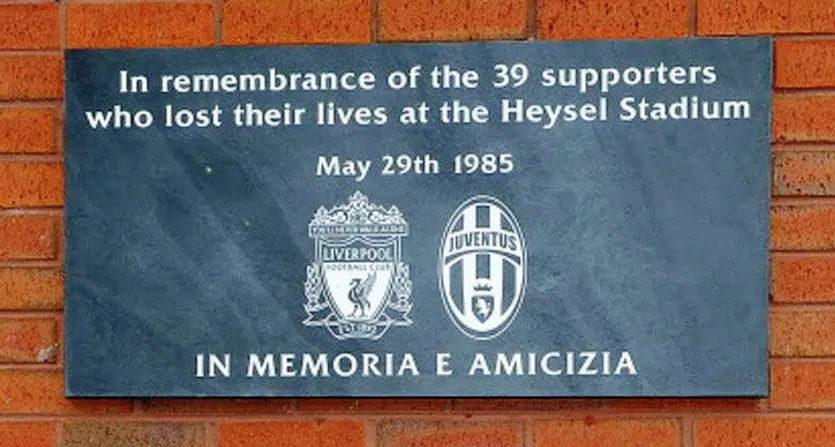

The Heysel stadium is named after King Beaudouin today, but that does not exorcise the haunting memory of European football’s darkest hour, when 39 mostly Italian supporters died in the Brussels football stadium in a stampede after Liverpool hooligans had invaded the section reserved for Juventus supporters just before kick-off of the European cup final. Six hundred more were severely injured.

Whatever the name given to it – ‘disaster’, ‘massacre’, ‘tragedy’ – the Heysel is a European traumatism. The ‘live televised death’ as La Repubblica labelled it, left a deep mark on the millions of Europeans that had switched on their television set in excited anticipation for what was expected to be a summit of European football culture. As Michel Platini, who scored the decisive goal in the match that took finally place despite what happened around the pitch, declared in 2010, no one who witnessed this tragedy ‘will ever be able to erase it from their memory’.

In an excellent chapter in a recent book on European football memory (1), Clemens Kech describes how the simultaneous Europe-wide media coverage turned this event first into a collective experience perceived to be massively shared across national borders, then into a genuine ‘European site of memory’ by making a European public engage in the discussion and evaluation of what had happened.

He also shows how over time the interpretation of the event slowly changes. At first, there is a strong emphasis in public debate on the archaic barbarism and brutal savageness displayed on that day. Among the different emotions triggered by this perception, the most powerful is no doubt a sort of collective shame across the continent, a reaction that comes close to the phenomenon of ‘moral panic’. Most importantly, this panic was felt and expressed by a clearly transnational public despite the well-known linguistic and cultural barriers within the European media landscape. Emotions were explicitly expressed in the name of ‘European values’ or ‘European civilization’.

Years later, in the collective commemoration of the event – whose remembrance is never completely extinguished but regularly activated with peaks every five years – the symbolic value assigned to it started to shift towards issues of crowd control and security issues. From today’s perspective, ‘the Heysel’, whose impact was reinforced by other disasters like ‘Hillsborough‘ (1989), marks a turning point in the organisation of large football events. It may be considered a watershed not only in the perception of football violence in general, but also in international cooperation on European level with regard to stadium design and regulations, crowd policing and spectator safety.

One way or another, the Heysel, which has a wikipedia entry in over twenty languages, will continue to be remembered as ‘a symbol of manmade tragedy’ as Clemens Kech summarises. It has become a reference point in the history of a common, transnational culture.

(1) European Football and Collective Memory, edited by Nils Havemann and Wolfram Pyta, London: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2015, published within the ‘Football in an Enlarged Europe’ book series.