25 May 2020

Report by Maximilian RECH & XIANG Jie

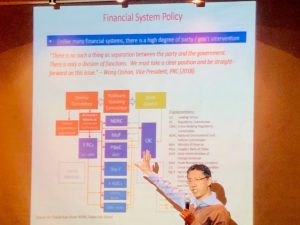

In contrast to most other developed countries around the world, there is a high degree of government intervention in China’s financial system. As a result, it remains difficult to understand for outsiders. It was, therefore, more than helpful to benefit from the detailed insight provided by Han Lin, Deputy General Manager of Wells Fargo in China, and Senior Relationship Manager of Global Banking China, speaker at the latest public event organised by ESSCA School of Management-Shanghai and China Crossroads on Sunday evening, 25 May 2020. Han Lin discussed the trajectory of China’s financial system and explored its implications for China’s integration into the international financial architecture. He opened by showing how policy reform in China is a function of various tendencies, including reviews and adaptations of the political system and legal systems as well as consecutive waves of anti-corruption campaigns. These developments also shaped the financial system and led to what Lin referred to as the ‘impossible trinity’, that characterises China’s financial system today and has implications for banking, capital markets and Fintech in the People’s Republic.

Recap: The Chinese Financial and Banking System

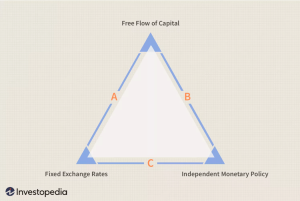

The Impossible Trinity

Capital control

China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchanges (SAFE), strictly controls the amount of foreign currency crossing the borders in and out of China. Thereby, SAFE manages the country’s foreign reserves; especially the US dollars (USD). For China, this is a matter of national security, because almost all global trade is denominated in USD. Essentially, China allows foreign investors to come in and leave as they please, but it is very dependent on the capital they accumulate in the country. Therefore, trade-related activities are encouraged and even warmly welcome, while capital account transactions are limited and capital outflow is highly regulated.

Exchange Rates

China is well aware of the weakness that consists of the dominant currency for international transactions always being the USD while the costs are denominated in Renminbi (RMB), the Chinese currency. This foreign exchange risk is complicating policy choices and China, therefore, seeks to internationalise the RMB. China actually created a payment system called CIPS, or Cross-Border International Payment System, and offshore RMB markets more than a decade ago. However, after 10 years of RMB internationalisation, it is still only the fifth reserve currency representing only 1.96% of all foreign reserves in Q4 2019 according to the IMF – too little to be a success story.

Monetary Policy

While debt remains an important and sometimes worrisome issue in China, Han Lin highlighted that China’s rapidly rising debt levels are sustainable for the time being as most debt is continuing to finance productive investments, such as infrastructure. One can, therefore, argue that there is a relatively low probability of a financial crisis caused by debt in China. Even if the total debt to GDP ratio has risen, the average debt to asset ratio has declined. This is an interesting argument that resonates with other emerging markets. The counter-argument is that China got to this level too fast. A mass of debt will lead to currency depreciation – especially in a moment of continued capital outflow, which refers back to the lessons learned from the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Therefore, China is really adamant about keeping control of debt. Han pursued his estimation of the likelihood of a financial crisis in China. He pointed out two conditions to trigger a financial crisis, namely mountains of debt and a formal catalyst, in other words: an event that forces borrowers to either repay their debt or declare bankruptcy. This is not really an option in China, because of differences in corporate governance and the oversized role of the state in the economy. China retains multiple mechanisms to control the process including regulations on non-performing loans and capital controls. “Will there be a crisis in China? Yes, it is quite possible, but it will be a little bit more difficult than what we have seen in the US. China is aware of the dangers and remains very cautious,” Lin added.

The Future of Capital Markets in China

In a 2017 financial reform, China tried to open up the market and allow foreign investors to have a larger equity stake in China’s financial market. More participation of foreign capital, it was hoped, would make the debt market more liquid. Securities, insurances as well as banking, asset management and venture capital (VC), all got liberalised in this reform. Lin then elaborated the proposed rules for all sectors above and cautioned that the market share for foreign banks actually went down from 2% to 1.7%. According to Lin, there are various opportunities in different sectors:

- Insurance – Offers an interesting possibility given depressed valuations of actors such as Anbang Insurance. The industry cleaned-up and now experiences double-digit growth in premiums.

- Banks / Securities / Brokerages – Here, an inverse relationship can be observed. Stronger domestic players limit interest in foreign ownership.

- Asset Management – Large scale opportunities for asset gathering & active investment.

- Venture Capital – This sector is slowing down, but continues to receive strong support at the government level – especially for tech-related investment. There is also a lack of a level-playing field for foreign VCs since certain areas such as social media remain off-limits.

FinTech

In this field, according to Han Lin, “the future is going to look very interesting”. He listed four key drivers of FinTech and emphasised that consumer-centric evolution and acceleration are key reasons for China to be keen on FinTech. In particular, it may lower barriers to market entry, provide affordable infrastructure, lead to new currencies and credit systems, and ultimately accelerate everyone’s access to finance. China’s embrace of FinTech is shaped by strategic goals and considerations. Providing a number of mini-case studies, Lin illustrated why FinTech engenders both hope and fear. The sector is characterised by experimentation, for example with regards to the establishment of a formal digital currency using the blockchain architecture. Such a digital currency would still remain under the control of the People’s Bank of China. “If the experiment continues, China may take the lead on digital currency and that would change the world in many ways.”

Further reading:

- Bloomberg – China Opens Up Financial Sector to More Foreign Investment

- Fortune – China’s Fintech Revolution—The Ledger

- Financial Times – China’s monetary policy stymied by “impossible trinity”

- The Wall Street Journal – The ‘Trilemma’ According to China’s Central Bank