- Moral rectitude would be the property of a state of things produced by moral virtues.

This answer is suggested by at the end of Google’s text presenting its seven principles in terms of artificial intelligence:

“We believe these principles are the right foundation for our company and the future development of AI.”

The term “right” conveys ideas of rectitude or righteousness. According to this first interpretation, moral rectitude would be a property of a state of things produced by moral virtues. To understand what this property might look like, it is useful to draw a parallel with “integrity.” In accordance with its etymological meaning, integrity refers to “the quality or state of being complete or undivided” (1), e.g. the result produced by an action. Linda Trevino and Katherine Nelson thus recall that it is a state, and they draw a practical consequence on professional ethics:

“Integrity is defined as that quality or state of being complete, whole, or undivided. So the ultimate idea is […] that a business person can be equally ethical at the office and at home.” (2)

The analogy of moral rectitude with integrity is based on the general scope of that quality or state, on the fact that it attaches itself to the person as a whole.

- Moral rectitude is close to, or equivalent to, integrity.

Alan Montefiore proposes a definition of integrity which is similar to that of Trevino and Nelson. But it gives this quality a more substantial and, above all, intrinsically moral character:

“A state of integrity is a state of wholeness that has not been broken or corrupted; a person of integrity is a person in one piece, who is responsible in the double sense that he can be trusted and is willing to be accountable for what he does or has done, a person who does not cheat with what he fundamentally defends.” (3)

The reference to “a person in one piece” suggests, on the one hand, that integrity is embedded in the character of a person, and, on the other hand, that the person is prepared to assume moral responsibility for his action. It is a person whose moral life follows a straight path in the sense of the Latin rectitudo, which means “direction in a straight line” (4). The “straight line” that is in question here links a person’s beliefs and commitments (“what he fundamentally defends,” Montefiore says) and the fact that he is unambiguously assuming responsibility. Two remarks. Firstly, it should be noted that Montefiore does not see integrity as a “virtue of form,” as John Rawls suggests (5). The latter qualifies it as such because, in his opinion, integrity can be used to serve a bad end. A tyrant (the example he proposes) could possess the virtue of integrity. Secondly, this interpretation assumes that moral rectitude is a virtue, or even a set of virtues (6). However, rectitude seems to be too general in scope to be qualified as “virtue.” The Dictionnaire historique de la langue française Le Robert states that it is the “quality of a person who does not deviate from the right direction, in the intellectual and moral field.” However, a virtue must relate to, or apply to, a particular field. Generosity, for example, refers to the act of giving wealth in a context where it is limited. But what would be the scope of moral rectitude? If we affirm that it is “the planning of one’s life and conduct,” we confuse it with the virtue of “prudence” or “practical wisdom” (7). Domènec Melé’s comment that “practical wisdom (prudence, in a moral sense), which […] helps one to judge with moral rectitude, is acquired over time,” avoids such confusion by reducing rectitude to a property of the judgment (8) – in the words of Monique Canto-Sperber : “To do well is to manifest by one’s act the rectitude of one’s deliberation and choice, the order of one’s soul, the truth of the rule one has followed and the correct orientation of one’s desire” (9).

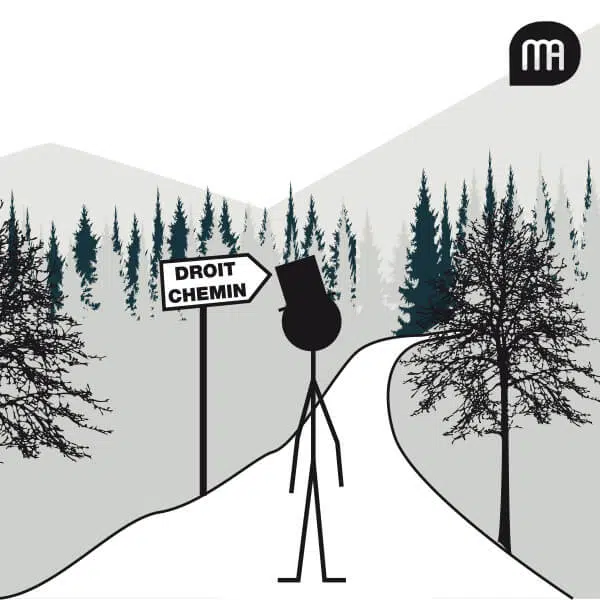

- Rectitude would be a property of the “path of life.”

The third interpretation is based on an objectivist conception of moral rectitude. This refers to a normative order to which everyone should conform in order to conduct their existence. Moral rectitude would be the property of the ideal path that every human existence should follow. The reference to the “path” is more than an allusion. Indeed, the path is constitutive of the idea of rectitude. Rectitude refers, in the literal sense, to the “character of what is straight or at right angles,” and, in the figurative sense, to the “intellectual or moral quality of a right person, the quality of a human faculty that conforms to reason, to the law, to the true norm” (4). The word “path” itself reproduces the two meanings of rectitude, as highlighted in the Dictionnaire historique de la langue française Le Robert:

“It has a figurative or metaphorical meaning based on the assimilation of the unfolding of life to a path to be followed (the path of life). Most often, locutions evoke an idea of progression towards a goal (to gain ground) or evoke the symbolic opposition of the straight line (the right path) and the curved line or abnormal path (a side-road).”

The sacred texts give many examples of this. In the Old Testament, the book of Proverbs reads as follows:

“I instruct you in the way of wisdom

and lead you along straight paths.” (10)

Moral rectitude is a property of the “path of life,” that is, to express it in Greek terms, of “living well.” ♦ Let us conclude by returning to the ethical commitments of Amazon, Google and Microsoft. If they exhibit moral rectitude, it is probably because of interpretation number three. These companies want to walk the “right path,” to follow the “path of rectitude.” And if the President of Microsoft, like other colleagues (11), has called for legal regulation of facial recognition programmes (12), he has in fact called for a path to be traced by a legitimate authority. As a result, he has accepted the idea – at least we can imagine this is so – that he is committed to following the right path: the path of moral rectitude. This should not be seen as a pure disinterested act. For what is important for an entrepreneur is first of all to move forward on a path and to continue on this path successfully. But if the path is tortuous and the voyage is dangerous, it is more prudent to choose the path of moral rectitude. Alain Anquetil (1) Source: Merriam-Webster. (2) L. K. Trevino et K. A. Nelson, Managing business ethics: Straight talk about how to do it right, New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1999. (3) A. Montefiore,“Identité morale,” in M. Canto-Sperber (ed.), Dictionnaire d’éthique et de philosophie morale, Paris, PUF, 1996. My translation. (4) See CNRTL (in French). (5) J. Rawls, A theory of Justice, Harvard University Press, 1971. (6) That’s how Rawls sees it. Integrity includes “truthfulness and sincerity, lucidity and commitment, or, as some say, authenticity” (op. cit.). (7) M. C. Nussbaum, “Non-relative virtues: An Aristotelian approach,” Midwest studies in philosophy, 13, 1988, p. 32-53. “Ability of the virtuous person, [prudence] guides moral virtue by indicating the means to achieve their ends,” Pierre Aubenque writes in “Aristote,” in Dictionnaire de la philosophie antique, Les dictionnaires d’Universalis, 2017. My translation. (8) D. Melé, Management ethics. Placing ethics at the core of good management, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. (9) M. Canto-Sperber, Ethiques grecques, Paris, PUF, 2001. My translation. (10) “Get Wisdom at Any Cost,” 4.11, The Holy Bible, New International Version, Zondervan, 2011. (11) See “Mark Zuckerberg: The Internet needs new rules. Let’s start in these four areas,” The Washington Post, 30 March 2019. (12) See my previous article. [cite]